Safer Streets – a whole system approach to Youth Crime

- Jul 29, 2025

- 5 min read

Achieving the government’s Safer Streets mission relies heavily on improving collaboration across multiple agencies. While an increased focus on neighbourhood policing is a key enabler for this mission, it’s clear that simply investing in an increased police presence won’t be enough to address the wider pressures across the wider Criminal Justice System. As recently identified in Lord Leveson’s Independent Review of Criminal Courts (Ministry of Justice, 2025) [1], establishing and maintaining programmes requires coordination between police, mental health services, relevant central government and local authority agencies and substance misuse treatment providers. Where vulnerable individuals with more complex needs are involved, a custodial sentence is not going to be the right outcome, and wider interventions, diversion programmes and out of court resolutions need to play a greater role.

Diverting young people away from the criminal justice system is a clear example of where successful outcomes depend on timely and coordinated input from a range of partners. However, despite their common purpose, many of these partnerships struggle with limited visibility of data, inconsistent information-sharing practices, and fragmented processes across organisations. This contributes to delays in referrals, duplicated effort, and missed opportunities for early intervention and prevention.

As part of our ongoing support of Police Now’s National Graduate Leadership Programme, Principle One recently hosted PC Moli McGinnis from Lincolnshire Police, who supported our team in a short exploratory project to examine information flows between agencies to support decision-making when young people come to the attention of the police.

Youth diversion is a complex and resource-intensive area of policing. It depends on close coordination between police, local authorities, education providers, health services, and a range of third-party organisations. These agencies must work together to design and deliver tailored interventions that reduce the risk of reoffending and support positive outcomes for young people.

Combining Moli’s experience of her own force with that of our consultants, we were able to validate our understanding of both the range of processes and different ways of working across forces and the systemic barriers in place to achieving efficiencies with different organisations working across a range of different systems. Although the work focused on a specific youth justice setting, the challenges observed are common across multi-agency services and the wider use of interventions such as out of court resolutions. Three recurring themes emerged:

Disparate Systems with Limited Interoperability

Each agency involved in multi-agency decision making typically uses its own case management or data system. These systems are designed for different purposes, developed at different times, and rarely connect in a way that allows for a shared view of a person’s history or current interventions. This lack of interoperability complicates coordination and limits visibility across services.

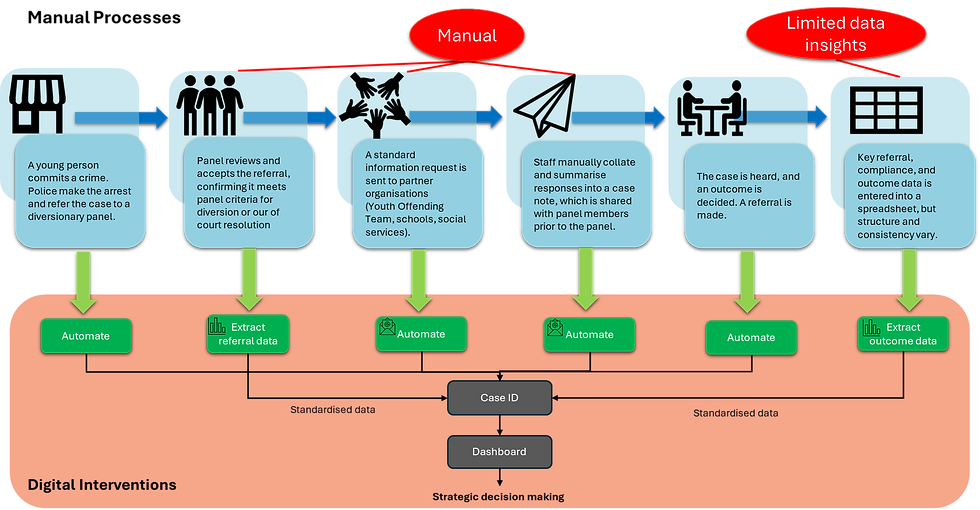

Manual Processes and the Risk of Delay

Without integrated systems, frontline staff often rely on manual workarounds such as email, Word documents, and verbal updates to share information, with data often keyed in multiple times. These approaches are inconsistent and lack standardisation, making it difficult to track progress or ensure consistent decision-making. They also increase the risk of delays, especially where information is incomplete or not shared, and can prevent the right interventions being put in place in a timely manner.

Fragmented Data and Limited Use of Management Information

As information is spread across unconnected systems, it is difficult to consolidate data in a way that supports operational or strategic decision-making. Access to meaningful management information is often limited, reducing the ability of agencies to monitor outcomes, assess risk effectively, understand capacity or even which intervention works in different situations.

This Discovery work highlighted how improved systems and processes could support the staff who are working across the agencies involved. While deeply committed to improving outcomes for young people, their efforts are often constrained by manual processes, fragmented systems, and limited visibility across agencies.

With systems having developed on a piecemeal basis against local ways of working, there is no straightforward 'one size fits all' solution. Interventions need to take into account local processes and interfaces to existing systems that are needed, but there are still some key areas where better integration and information sharing could offer significant benefits.

Streamlining Case Preparation

Multi-agency coordinators currently spend significant time manually requesting and compiling background information before each panel. Introducing process automation tools, such as generating and sending standardised digital information requests to partner agencies, could improve consistency and reduce duplication, collating returned information into case summaries that could then be shared in advance to multi-agency panel members.

Improving Oversight of Referrals and Engagement

Once a decision is made, it is vital that all agencies involved can see whether a young person has engaged with the recommended support. A shared referral and monitoring tool that is accessible to police, youth offending teams, and third-party providers would streamline the referral process. It would enable users to create referrals, confirm service uptake, monitor engagement, and identify non-compliance early. This would enable more joined-up working and improve accountability across the process.

Building a Shared Evidence Base

Improving how data is collected, shared, and used across agencies is a fundamental enabler of more effective decision-making. Creating a standardised data model to record panel decisions, referral outcomes, and service engagement would help inform both operational delivery and long-term strategy. Better data management would allow multi-agency panels to identify and address service gaps or duplication, track outcomes and support evidence-based practice and make timely, informed decisions that reduce risk and harm.

Each of these initiatives also supports the national focus on evidence-based policing and youth justice strategies focused on long-term outcomes and aligns with wider NPCC-led initiatives. From Moli’s perspective, the secondment was a chance to step back from the pressures of frontline policing where her focus is on tackling the next case in front of her. “I’ve been able to gain valuable insight into the broader challenges faced by policing, criminal justice systems and the civil service as a whole. It’s opened my eyes to the complexity of multi-agency working and the importance of wider collaboration - perspectives that are often difficult to see from the frontline. This experience has deepened my understanding of how different parts of the system connect and the crucial role each plays in driving change.”

The issues identified here reflect a broader challenge facing many public services: while the commitment to work collaboratively is strong, the systems and processes underpinning that work are often fragmented, manual, and not designed with collaboration in mind. As part of the Independent Review of Criminal Courts, the need for wider deployment of digital tools and solutions, is acknowledged, given the potential to reduce the overall time from offence to resolution and often halt escalations in criminality.

Improving collaboration does not require large-scale change all at once. Instead, targeted improvements, supported by the right tools, shared accountability, and a commitment to learning, can lead to meaningful progress. Even small projects like this secondment can generate valuable insights and lay the groundwork to drive change at a national level.

[1] Ministry of Justice (2025) Independent review of the criminal courts: part 1. London: Ministry of Justice. Available at: Independent Review of the Criminal Courts: Part 1 - GOV.UK

Comments